|

The

Capitol Records biography from October 1995 said it perfectly: “John Hiatt

has long occupied a singular place among American singer-songwriters. He’s

an artist who twists rock and soul and blues and R&B into rhythmic shapes

that echo the deep and surprising way he sees things.”

As Hiatt himself says: “I’m a songwriter but I’m also a guy who has to

perform his won material. I write my own stuff, but it’s ultimately all

about music, melody, my technique. I’m always interested in sound. You’ve

got to inhabit the right sonic space for the song to resonate with any

meaning.”

Hiatt’s songs have resonated with meaning for more than two decades and

whilst it’s fair to say that it was late ‘80’s albums like Bring The

Family (1987), Slow Turning (1988) and Stolen Moments (1989) that really

bought him to a substantial world-wide audience those and subsequent

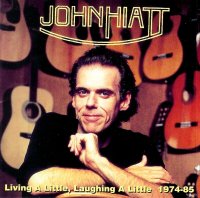

albums only tell part of the story. Living A Little, Laughing A Little

collects much lesser known material from 1974 to 1985 that are a sublime

example of the evolution, development and increasing maturity of a truly

inspired writer and performer.

Born and raised in Indiana, Hiatt started writing songs at the age of 11.

He estimates his total output over the years at well of 600 songs. Intent

on making a career of it, Hiatt left high school to work as an in-house

writer for Tree Publishing in Nashville.

Aside from a 1972 recording, In Season by White Duck – about which Hiatt

train-spotters will doubtless know more than I – Hiatt’s first recording

under his own name was Hangin’ Around The Conservatory which was released

by Epic Records in 1974.

As Hiatt commented at the time: “One night, we went up to this observatory

where once a month people are allowed to come in and view the stars. It

was way up on top of a hill out in the country. On the way up, I got the

feeling I was going to visit a mad scientist’s house…I feel like I’m an

observer. I’m not really here; I’m watching.”

On the sleeve notes for Observatory Bruce Harris observed: “Without ever

losing its central distinctiveness, John Hiatt’s music can be heavy or it

can be lyrical. It can be metal or it can be magical. Always, it is music

filled with spirit, energy, humour, and excitement. And of course, John’s

strangely compelling voice is the perfect match for the curious music and

more curious lyrics. Hiatt’s not just strange – these days, it’s easy to

be weird. Hiatt takes it one step beyond; like the truth, he is stranger

than fiction.”

In the Village Voice Robert Christgau decided the album was worth a ‘B’

which given his legendary toughness and bizarre idea of rating every album

with a letter, wasn’t too bad. And certainly Christgau was one of the

earliest critics to recognize that Hiatt had a lot to offer: “Hiatt is a

Mid-western boy who wrings off center rock’n’roll out of a voice with lots

of range, none of it homey. Reassuring to hear the heartland Americana of

the Band actually inspire a heartlander. Reassuring too that one of the

resulting songs can be released as a single by Three Dog Night.”

Observatory didn’t, however, make too much of an impression and it was

followed a year later by Overcoats an altogether more impressive outing –

although not everyone agreed. These days it’s easy to think of Hiatt as a

critic’s favorite as his albums are consistently lauded but that’s

certainly not always been the case. None other than Dave Marsh has written

(in the first Rolling Stone Record Guide, 1979) of Overcoats: “Hiatt is

about as ill at ease and forced as an R&B-based white singer/songwriter

can get, which is awfully ill at ease and horribly forced. One suspects

that Overcoats, released in 1975, will soon go the way of Hiatt’s

out-of-print debut LP.”

Again Robert Christgau was far more complimentary – but still rated the

album a ‘B’: “I admit to a weakness for loony lyrical surrealist protest

rockers. And I admit that this one tends to go soft when he tries to go

poetic. I even admit that he has a voice many would consider worse than no

voice at all (although that’s one of the charms of the type). But I insist

that an7yone who can declaim about killing an ant with his guitar

‘underneath romantic Indiana stars’ deserves a shot at leading-man status

in Fort Wayne.”

During this period Hiatt hit the road, touring fold venues and festivals

across North America, and building a loyal club following in the process.

By 1979 he had moved to Los Angeles and was signed to MCA after becoming a

notable part of the New Wave scene.

By the time Hiatt had released three more albums – Slug Line (1979),

Two-Bit Monsters (1980) and All Of A Sudden (1982) Marsh was coming around

to realizing that maybe there was something going on here – but he sure as

hell wasn’t certain what it was: “Hiatt’s strained soulfullness always

overcomes his wise-guy charm, at least in these quarters. Indeed, if one

weren’t so certain of Ry Cooder’s taste (and if Hiatt weren’t a member of

Cooder’s recent bands), the temptation would be to dismiss this pompous

posturing as a fairly vile example of post-Springsteen bombast. However,

faith assures us something must be there. Possibly by the next edition it

will be located in more than association.”

With Slug Line Christgau decided that Hiatt was actually worth a ‘B+’.

Things were definitely looking up: “This hard-working young pro may yet

turn into an all-American Elvis C. He’s focused his changeable voice up

around the hegh end and straightened out his always impressive melodies,

but he has a weakness ofr the shallow (if sincere) putdown, e.g.: ‘You’re

too dumb to have a choice.’ Or else he;d get chosen, do you think he

means?”

A far more supportive early champion of Hiatt’s was Trouser Press editor

Ira A. Robbins but even he described the first two Epic albums as

“unextraordinary, mild singer/songwriter records.” For Robbins Slug Line

was the album where Hiatt first displayed what he was potentially capable

of. He considered that Hiatt was “a fiercely original, soul-inflected rock

character, likened to Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson, but wholly his own

man.”

In between making his own albums Hiatt had always found time for other

projects. In 1976 ther was Don’t It Make You Want To Dance? with Rusty

Weir, and in 1980 the acclaimed Borderline soundtrack with Ry Cooder. The

same year saw the release of a promotion only live album, unimaginatively

titled Border Live. During 1980 Hiatt also contributed the song Spy Boy to

the soundtrack of the film Cruising.

The year 1982 was a new album in the Tony Visconti-produced All Of A

Sudden, a performance with Ry Cooder on Slide Area (Geffen), and a

substantial contribution to The Border soundtrack.

Riding With The King, produced a side each by the Durocs team of Ron Nagle

and Scott Matthews, and by Nick Lowe, was released in 1983, the same year

that saw him singing backing vocals on Richard Thompson’s Hand Of Kindness

album.

It wasn’t until 1985 that Hiatt released any new material – first a

powerful and well-realized new album Warming Up To The Ice Age, which

would be his last for Geffen before signing with A&M and releasing Bring

The Family. During 1985 Hiatt also released a single, Living A Little,

Laughing A Little, backed with two rare live tracks – When We Ran and

Everybody’s Girl. There was also a promotional-only live album, Riot With

Hiatt, backing vocals with Los Lobos on Will The Wolf Survive and more

contributions to film soundtracks.

Since the mid ‘80’s Hiatt has appeared on record with Peter Case, Rodney

Crowell, Loudon Wainwright III, Nick Lowe and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.

And it hasn’t stopped – Hiatt makes his own superb albums but is no slouch

when it comes to keeping busy in between and lending a hand to recordings

by the most disparate of artists. In 1990 he sang and played whistle on a

track from Ben Vaughan’s Dressed In Black album, and provided backing

vocals on Something Wild from Iggy Pop’s Brick By Brick album.

Then there’s Hiatt’s other career as a songwriter. There is an

extraordinarily diverse array of artists who have recorded his songs, with

no more than 60 different individuals considering their records would be

just that little better with the inclusion of at least one Hiatt song.

Among those acts are Bob Dylan, the Neville Brothers, David Crosby, Joe

Cocker, the Jeff Healey Band, Steve Earle, Dave Edmunds and Paula Abdul.

More than two decades after he started his songwriting and recording

career John Hiatt stands as one of the most distinctive and passionate

reformers in contemporary music. He’s undergone a transformation from

angry ‘70’s new waver to tasteful, spirited roots rocker with class and a

whole lot of heart’n’style. On a recent American TV show, The Hot List,

Hiatt talked of and listed his personal ‘desert island’ favorite albums,

which gives a fine insight into the music that has shaped his own. In

descending order from one to five Hiatt’s selections were Marvin Gaye &

Tammi Terrell’s Greatest Hits (Hiatt mentioned how much he loves the

Ashford & Simpson songwriting team), Bob Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde, Sly &

The Family Stone’s Fresh, The Band’s self-titled album, and Jimi Hendrix’s

Axis: Bold As Love.

Contained on this album are classic recordings from Hiatt’s formative

periods. Rarely less than enthralling they are a vital part of Hiatt’s

story – one of great songs, distinctive vocals and a real rock’n’roll

heart that’s worn proudly on the sleeve.

Moreover this sleeve notes suggest that at least one companion volume

colleting many of Hiatt’s other sideline projects, collaborations and

soundtrack work would be, well, a damn fine idea. Coming soon to a record

store that cares.

Stuart Cope, 1995 |